Academia and the media usually view Darwin’s theory of evolution as a fact, a concept so thoroughly established as to be beyond serious challenge. Yet when Dr. Wayne Detmer, a good friend who is now working at an inner city medical clinic in Chicago, attended his Introductory Biology class at Yale, the professor asked the students: “How many people here believe that God created man?” Just a few hands went up, six or so, out of about 150. The professor then said, “I have to admit that it takes as much faith to believe in evolution as it does to believe that God created man.”

That professor is not alone in having doubts. In November 2007, The New York Times ran an article entitled “Taking Science on Faith.” The article pointed out that both religion and science require faith. “All science proceeds on the assumption that nature is ordered in a rational and intelligible way… The most refined expression of the rational intelligibility of the cosmos is found in the laws of physics, the fundamental rules on which nature runs…. But where do these rules come from? And why do they have the form that they do?” (Davies, Nov. 24, 2007)

Before getting into evolution, consider the meaning of the word “science.” Webster’s, New World Dictionary defines science as, “systematized knowledge derived from observation, study, and experimentation carried on in order to determine the nature or principles of what is being studied.” (Webster’s, 1305). Within its realm—inferring theories from observable facts—science is marvelous. However, the greatest scientific problem with investigating the origin of life and the universe is that none of us were there. We cannot go back in time nor accurately reproduce the conditions under which life began, let alone how it developed thereafter.

If archeology is forced to draw its conclusions based on a fraction of the original evidence, how much more must the study of origins make educated guesses based on trace evidence left behind over the ages.

In teaching Advanced Placement Statistics, I warned my students about conclusions based on extrapolation: estimating the unknown on the basis of known behavior. Extrapolation can produce highly misleading and unreliable conclusions, conclusions that are handled cautiously in all fields—except, it seems, in the study of origins. We can only estimate what happened in the development of life and why, with a large margin of error. A measure of humility is required, therefore, of any person investigating such matters, as reflected in the Lord’s words to Job in chapter 38, verse 4, “Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundation?”

We should also define here what we mean by the word evolution. There are actually two very different types or levels of evolution: micro-evolution and macro-evolution. Micro-evolution is hardly controversial at all. It simply describes that built in capacity of all living organisms to adapt to their environment, and to accumulate favorable but relatively minor changes over time. It happens to individual organisms within a species, or among species within the same genus. Ironically, the case studies that Darwin includes in his classic work, The Origin of Species, involve only micro-evolution. A perfect example is the natural selection of a darker moth over a lighter one in the face of air pollution in 19th-century England. The lighter colored moths clinging to the side of a soot-covered tree were more visible to birds, while the darker moths were more likely to escape becoming lunch, so the darker moths prevailed. Ironically, with cleaner air in London since Darwin’s day, the lighter colored moths have re-appeared. Overall, however, when all such adaptive changes have occurred, a moth is still a moth.

Macro-evolution is more controversial in that it involves the claim that accumulated small changes, what Darwin described as “numerous, successive, slight modifications” over sufficient time can entirely explain the development of every living organism on earth. In Prof. Michael Behe’s words, “In its full-throated, biological sense, evolution means a process whereby life arose from non-living matter and subsequently developed entirely by natural means. That is the sense that Darwin gave to the word, and the meaning that it holds in the scientific community.” (Darwin’s Black Box, pp. x-xi) Darwin insisted that the development of all life can be traced backwards through time along the branches of a single tree descending from a single root, something he called “the great Tree of Life.” Ironically, the “tree of life” is a Biblical metaphor, but as Friedrich Nietzsche pointed out, Darwin’s aim was the “calm annihilation of the fairy-tale fable of the Creation of the World.” (Peter Quinn, “The Gentle Darwinians,” 8)

From this point on, when I use the word evolution, I am speaking of macro-evolution. While the intelligence of those who question this form of evolution for religious reasons (or even academic ones) is popularly ridiculed, many scientists and others who hold to the theory of evolution guard their turf with a religious zeal that is itself suspect. A Chinese paleontologist wrote to Phillip Johnson, the author of Darwin on Trial, “In China we can criticize Darwin but not the government. In America, you can criticize the government but not Darwin.” (World Magazine, 2/26/00, 32)

The Oxford zoologist and champion of evolutionary science, Richard Dawkins, wrote that, “Darwin made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist,” that is, Darwin’s theory supported his particular perspective on religion. While critical of the “intolerance” of creationists, this same man also exclaimed, “It is absolutely safe to say that, if you meet somebody who claims not to believe in evolution, that person is ignorant, stupid or insane (or wicked, but I’d rather not consider that)” (Johnson, 9).

The Origin of The Origin

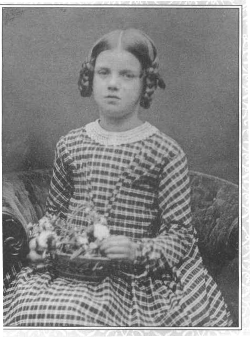

Darwin’s motivation for writing The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection was itself not altogether scientific. Before his beloved daughter Annie died, he had held an essentially Christian view of the world, though a more naturalistic and materialistic perspective had been growing within him for years. When Annie died after a slow and painful bout with tuberculosis at the age of 10, Darwin refused to accept her death as something that the Almighty understood better than he did, and rebelled against a God he viewed as cruel for allowing such suffering. Darwin watched helplessly as his beloved Annie died a slow and painful death from tuberculosis. In his own words, “We have lost the joy of the household, and the solace of our old age…” (Keynes, 217) Darwin was a man who “did not separate his thinking about the natural world from the ideas and feelings he held about his family and the rest of his life.”

Annie Darwin in 1849

Annie Darwin in 1849

In his Introduction to Origin of Species, Charles Darwin wrote, “the view which most naturalists entertain, and which I formerly entertained—namely, that each species has been independently created—is erroneous” (Origin, 7). Unlike Job who, after losing his children, said, “The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be praised” (Job 1:21), Darwin determined to find an explanation for life and the universe that did not require the intervention of the God with whom he was so angry. In 1859, he wrote to Sir Charles Lyell, “I would give absolutely nothing for the theory of Natural Selection, it if requires miraculous additions at any one stage of descent” (Crews, 24).

In his recent book, Darwin, His Daughter, and Human Evolution, Randal Keynes, Darwin’s great-great-grandson, states that, “After Annie’s death, Charles set the Christian faith firmly behind him…. He did, though, still firmly believe in a Divine Creator. But while others had faith in God’s infinite goodness, Charles found him a shadowy, inscrutable and ruthless figure.” As a young man Darwin had “noted the ‘pain and disease in [the] world’ without further comment.” But when he returned to the theme in the years after Annie’s death, “he wrote about it in a new way. He never referred directly to his personal experience; that would have been quite inappropriate. But he made some new points; there was a darkness in the wording of some passages, and others echoed his feelings about human loss.” One of the most critical of these new points was the survival of the fittest: “Charles continued to work on the ‘laws of life,’ but was now sharply aware of the elimination of the weak as the fit survived” (Keynes, 243-4).

Another of the points Darwin focused on more resolutely was his view of man as an animal. His daughter Etty wrote after his death that his “habit of looking at man as an animal had become so present to him, that even when discussing spiritual life, the higher life kept slipping away.” In Keynes’s words, “Etty was right to suggest that this habit undermined his thinking about ‘the higher life’; he was developing his own ideas about human nature at the same time, deep rather than high, to put in place of the claims of Christianity” (Keynes, 252).

By the time Darwin wrote the The Descent of Man, the “darkness” in his views of man included a strong element of racism and even the promotion of eugenics. He admitted that there was a “great break in the organic chain between man and his nearest allies [the primates], which cannot be bridged over by any extinct or living species.” He also acknowledged that the existence of such a large gap had “often been advanced as a grave objection to the belief that man is descended from some lower form” (Descent, 200). Nevertheless, he was not at all troubled by the size of this gap. In fact, he anticipated that the break in the evolutionary chain would get even larger as the higher “races” of mankind actively eliminated the lower “races.”

Clearly, Darwin viewed Europeans as eminently superior to other races of men, especially people of color. Looking back from this side of the Holocaust, these are some very dark words indeed. If you ever wondered about the origins of the 20th century’s murderous theme of “racial cleansing,” you need look no farther than 19th century writings!

Opposition to The Origin

Darwin apologized at the beginning of Origin for not being able to include all the facts on which he based his conclusions, especially regarding natural selection. He admitted, “For I am well aware that scarcely a single point is discussed in this volume on which facts cannot be adduced, often apparently leading to conclusions directly opposite to those at which I have arrived” (Origin, 4).

What many do not know today is that the chief opposition to Darwin’s theory at its writing arose not from religious believers, but from scientists. Many of his fellow naturalists drew very different conclusions from the same set of evidence he used. As Dr. William W. Wassynger wrote in the “Letters” section of The New York Times on December 15, 1989, “Even in Darwin’s day, scientists who opposed evolution were charged with irrationality and religiosity. But they did not attack evolution on religious grounds; rather, they protested its lack of scientific proof and pointed to the evidence that supported a typological nature,” namely, the fossil record’s clear support for the classification of organisms by distinct types rather than by Darwin’s claim of common and gradual descent. (Wassynger)

Most geologists of the time believed in catastrophism, “the theory that geological changes have been caused in general by sudden upheavals rather than by gradual changes” (Webster’s, 230). Gradualism is critical to Darwin’s theory since, as he admitted, “If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down” (Origin, 158).

Richard Dawkins acknowledges that evolution may not be gradual in all cases, but states that it must be gradual when explaining “the coming into existence of complicated, apparently designed objects, like eyes. For if it is not gradual in these cases, it ceases to have any explanatory power at all. Without gradualness in these cases, we are back to miracle, which is simply a synonym for the total absence of explanation” (Behe, 40). At least it is an absence of explanation to an atheist!

Geologists like Benjamin Silliman of Yale, who examined the geological record at East Rock and elsewhere, had good reason to believe in catastrophism. Remember that fossils are not formed under typical circumstances, i.e., death followed by rapid decay of organisms. They are formed as a result of floods, volcanic eruptions, and other violent circumstances where the remains of living organisms are trapped suddenly at the time of death in such a way that the normal process of decay does not occur. The fossil record is itself the best evidence for catastrophism—and against Darwin’s idea of gradualism.

Creatures appear and disappear from the fossil record at regular intervals, with no evident connection to animals that preceded or followed them. As David Berlinski, a mathematician who spoke at Yale a couple of years ago, wrote,

(Berlinski, 19-20).

No wonder Darwin had to include in Origin a discussion of “the imperfection of the Geological Record” (chapter 9), that record standing so at odds with some of his claims. He claimed, regarding the absence of intermediate life forms, “that intermediate varieties… existing in lesser numbers than the forms which they connect, will generally be beaten out and exterminated during the course of further modification” (Origin, 230).

Exactly why those connecting forms should be in lesser numbers than surviving forms, rather than greater if Darwin’s claims are true, is open to question. The Nobel-prize-winning chemist and evolutionist Jacques Monod wrote, “Chance alone is at the source of every innovation, of all creation in the biosphere. Pure chance, absolutely free but blind, is at the very root of the stupendous edifice of creation” (Berlinski, 22). But, if this is true, then many intermediate forms would be required to produce the few random improvements that would actually survive. You cannot know what forms will be fitter until you try them.

How many times would you have to roll a die before you succeeded in rolling ten “ones” in a row? If that seems difficult, the improvement of an existing structure in nature by chance alone would require far more failed experiments, or intermediate forms, than successful ones. It cannot be assumed in any case that all the connecting forms would disappear in their entirety from the geological record.

Darwin himself admits, “Why then is not every geological formation and every stratum full of such intermediate links? Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely graduated organic chain; and this, perhaps, is the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against my theory. The explanation lies, as I believe, in the extreme imperfection of the geological record” (Origin, 230). As budding lawyers are sometimes instructed, when the facts are on your side, pound on the facts. When the facts are against you, pound on the table!

Theorizing on the Grand Scale

In Origin, Darwin claimed that all species of plants and animals developed from earlier forms by hereditary transmission of “slight differences accumulated during many successive generations,” that is, “the idea of species in a state of nature being lineal descendants of other species” (Origin, 26). Darwin goes far beyond this, however, in arguing that “the small differences distinguishing varieties of the same species, will steadily tend to increase till they come to equal the greater differences between species of the same genus, or even of distinct genera…. On these principles, I believe, the nature of the affinities of all organic beings may be explained. It is a truly wonderful fact… that all animals and all plants throughout all time and space should be related to each other in group subordinate to group… the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth” (Origin, 108-10). Note that Darwin’s claims here involve quite a leap of faith!

It is generally agreed that some form of evolution, variation or micro-evolution, occurs within species or even to some extent within genera, or genuses. But Darwin’s theory runs into major difficulties when he claims that evolutionary change can produce different categories of living organisms from the same root, i.e., macro-evolution. To defend his claim that all life came about through a single, entirely natural line of descent (his “great Tree of Life”) requiring no intelligent or divine intervention, he set up a kind of “straw man” argument against his contemporaries who believed in a Creator, exaggerating their views on the immutability of species. He writes of, “He who believes that each being has been created as we now see it,” or of “He who believes in separate or innumerable acts of creation” (154-55), or even “if we look at each species as a special act of creation” (48), negative and scornful descriptions that do not begin to do justice to the views of those who opposed his theory.

The Bible states that God made all creatures according to their types or kinds, but variation within those types is in no way precluded. Note for a moment the fascinating wording that chapter one of Genesis uses in describing the origin of life: “Then God said, ‘Let the land produce vegetation: seed-bearing plants and trees on the land that bear fruit with seed in it, according to their various kinds‘” (Genesis 1:11). Later on we read, “And God said, ‘Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth’… according to their kinds” (1:20-21) and again, “Let the land produce living creatures according to their kinds” (1:24, italics added throughout). Nothing in the wording of Genesis 1 requires that “according to their kinds” equates kinds with what scientists call species. The Hebrew word for kind means “to portion out,” or to sort. We are hardly given every last detail of what happened but, though it is clear that the various types of creatures were distinctly created and “sorted out” from one another, this is not a description of “each species” being “a special act of creation,” or “that each being has been created as we now see it.”

In any case, it is not at all surprising that a loving Creator would build an amazing adaptability into the genome of each category of plant or animal He made, giving them an ability to survive over time under changing circumstances. Consider the words of Yale’s Benjamin Silliman, generally viewed as the father of American scientific education, and a brilliant man with a very different worldview than Darwin. In his Reminiscences he wrote, “I can truly declare, that in the study and exhibition of science… I have never forgotten to give all the honor and glory to the infinite creator, happy if I might be the honored interpreter of a portion of his works.” (Schiff, 80) If as Jesus said, “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from the will of your Father” (Matthew 10:29), one would expect a great deal of care to have gone into the making of each type of creature. The fossil record itself accords closely with this description of variation, demonstrating the adaptability of plants and animals within their various types, as in the varieties of horses that have existed over time.

Head Lice and Hippos—Distant Kin

But the fossil record does not show a horse turning into a giraffe! To quote the paleontologist Niles Eldredge,

(Behe, 27, emphasis added).

By the way, in the middle of Genesis’s description of creation are the words, “God blessed them and said, ‘Be fruitful and increase in number and fill the water in the seas, and let the birds increase on the earth'” (Genesis 1:22), a fascinating statement in light of what Darwin called “the principle of geometrical increase” of life (Origin, 55).

Various efforts have been made over the years to restate Darwinian theory and mend its many failings, including Neo-Darwinism, but in the words of the English biologists Mae-Wan Ho and Peter Saunders, “It is now approximately half a century since the neo-Darwinian synthesis was formulated. A great deal of research has been carried on within the paradigm it defines. Yet the successes of the theory are limited to the minutiae of evolution, such as the adaptive change in coloration of moths; while it has remarkably little to say on the questions which interest us most, such as how there came to be moths in the first place” (Behe, 28).

It is one thing to claim that a creature adapts to its environment according to its built-in capacity to do so. It is quite another to claim that a creature can adapt such that something entirely new is produced. Without the latter, the development of life would be impossible, at least without intelligent intervention.

In arguing his case for what he called “Natural Selection,” Darwin could offer no clear observable examples from nature of what he was describing, so he argued by analogy in his chapter on “Variation under Domestication” (Origin, Chapter 1). The irony here is, of course, that he is arguing the case for unassisted natural descent by appealing to variation in plants and animals under the guiding hand of human beings over long periods of time. Beyond that, however, the variations he describes are possible only because the capacity is already present in the genetic makeup of the organisms in question, whether sheep or hyacinths. Nevertheless, even breeding guided by humans has its limits. A hyacinth cannot be turned into an orchid.

In the words of the French zoologist, Pierre Grassé, “In spite of the intense pressure generated by artificial selection… over whole millennia, no new species are born…. The fact is that selection gives tangible form to and gathers together all the varieties a genome is capable of producing, but does not constitute an innovative evolutionary process” (Johnson, 18).

Contrast the limited ability of natural selection just described with Darwin’s claims. By “natural selection” he is referring to nature’s ability to select from among numerous variations, preserving “favourable variations” and rejecting “injurious” ones. Moreover, he claims that Nature “can act on every internal organ, on every shade of constitutional difference, on the whole machinery of life” (Origin, 71), thereby moving the process of evolution ever forward. “Over all these causes of Change I am convinced that the accumulative action of Selection… is by far the predominant Power” (Origin, 38). After describing the millennia of human attempts at breeding superior plants and animals, he writes, “We have seen that man by selection can certainly produce great results…. But Natural Selection… is as immeasurably superior to man’s feeble efforts, as the works of Nature are to those of Art” (Origin, 53).

Darwin did not stop there, however, for he wrote, “It may be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life” (Origin, 71). At the end of Origin he wrote, “And as natural selection works solely by and for the good of each being, all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress towards perfection” (Origin, 399).

Nature as God, or the God of Nature?

Doesn’t it strike you that, in trying to obviate the need for an intelligent Being’s involvement in the development of life, Darwin ascribes intelligence to Nature itself? In order to replace the Creator he no longer wished to deal with, he had to make Nature itself into a kind of demigod, an intelligent “force” set high upon a throne shrouded with a scientific aura. Whether you accept his claims or not, the result is the same. We have come full circle and are once again left facing the fact that, without intelligent intervention, life in all its beauty, variety, and complexity is impossible!

Consider then our modern tendency to acknowledge Evolution, or Mother Nature, or Father Time, or Mother Earth, etc., but not Almighty God. Consider this especially in light of what the apostle Paul wrote to the Romans almost 2,000 years ago:

(Romans 1:21-23).

In his Autobiography, Darwin wrote of his earlier years, “whilst standing in the midst of the grandeur of a Brazilian forest, ‘it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind.’ I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body.” Yet about his later years he writes, “But now the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions and feelings to arise in my mind.” (“Religious Belief,” Autobiography)

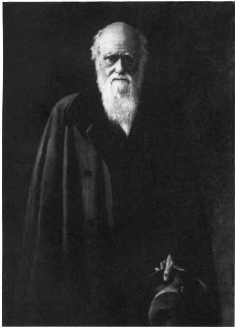

Charles Darwin in His Latter Years

Charles Darwin in His Latter Years

Nevertheless, scientists such as Stephen Jay Gould of Harvard were disappointed that, in their view, Darwin’s final months were spent in melancholy and listlessness (Milner, 75). He was unable to stout it out to the end of his days as a contented atheist, with chin held high. In fact, Darwin never did have an easy time maintaining his atheism. As the famous Oxford scholar, C. S. Lewis, has pointed out, being an atheist is quite difficult. “When I was an atheist I had to try to persuade myself that most of the human race have always been wrong about the question that mattered to them most…,” the existence of God (Lewis, 43) Darwin himself had increasing problems with psychosomatic disorders in the years after he published Origin of the Species. In his own words, he suffered from “extreme spasmodic daily and nightly flatulence: occasional vomiting… vomiting preceded by shivering, hysterical crying, dying sensations or half-faint… ringing of ears, treading on air and vision, focus and black dots, air fatigues, specially risky, brings on the Head symptoms, nervousness when E. leaves me.” (Quinn, 16)

E. was Emma Darwin, Darwin’s devout Christian wife. “My own wife ever dear Mammy, I cannot possibly say how beyond [sic] all value your sympathy and affection is to me.—I often fear I must wear you with my unwellness and complaints.” She never ceased to pray for her husband, that he would make his peace with her beloved Jesus. In one letter to her husband, she pleaded with him to at least read Christ’s farewell to his disciples in the Gospel of John: “It is so full of love to them and devotion and every beautiful feeling. It is the part of the New Testament I love best.” As Peter Quinn pointed out in March 2007 in his article, “The Gentle Darwinians,” “Sure as Darwin was that ‘man is more courageous… and energetic than woman,’ it was Emma’s courage and energy that held their family together and provided the stability and support he required to pursue his research and writing… Emma directed the servants, saw to the farm, supervised the children, and was a presence in the lives of her neighbors. Her kindness was legendary… ‘she understood human suffering.'” (Quinn, 16)

Emma’s prayers for her husband seem to have been answered in the last months of Charles Darwin’s life. According to the account of Lady Hope, a friend of the family who was with him during his final days in 1882, Darwin finally found the peace he had long searched for:

“What are you reading now?” I asked.

“Hebrews,” he answered, “‘The Royal Book’ I call it.” Then as he placed his fingers on certain passages, he commented on them.

I made some allusion to the strong opinions expressed by many on the history of the Creation, and then their treatment of the earlier chapters of the book of Genesis. He seemed distressed, his fingers twitched nervously and a look of agony came over his face as he said, “I was a young man with unformed ideas. I threw out queries, suggestions, wondering all the time about everything. To my astonishment the ideas took like wild-fire. People made a religion of them.”

Then he paused, and after a few more sentences on the holiness of God and “the grandeur of this Book,” looking tenderly at the Bible which he was holding all the time, he said: “I have a summer house in the garden which holds about thirty people. It is over there (pointing through the open window). I want you very much to speak here. I know you read the Bible in the villages. Tomorrow afternoon I should like the servants on the place, some tenants, and a few neighbors to gather there. Will you speak to them?”

“What shall I speak about?” I asked.

“Christ Jesus,” he replied in a clear, emphatic voice—adding in a lower tone, “and His Salvation. Is not that the best theme? Then I want you to sing some hymns with them. You lead them on your small instrument, do you not?”

The look of brightness on his face, as he said this, I shall never forget; for he added: “If you make the meeting at three o’clock, this window will be open, and you will know that I am joining in with the singing.”

(Myers, 248, emphasis added)

Copyright ©2008 Christopher N. White

(Originally published in The Yale Standard, April 2002, an evangelical publication on the Yale University campus. Updated for a presentation on Darwin, Evolution and God given at Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia, January 24, 2008)

Bibliography:

1.) Michael J. Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, The Free Press, New York, 1996.

2.) David Berlinski, “The Deniable Darwin,” Commentary, June 1996, 19. 3.) Frederick Crews, “Saving Us from Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, Oct. 4, 2001, 24.

3.) Frederick Crews, “Saving Us from Darwin,” The New York Review of Books, Oct. 4, 2001, 24.

4.) Charles Darwin, “Religious Belief,” The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, (Nora Barlow, ed., 1958), available at http://www.update.uu.se/~fbendz/library/cd_relig.htm (visited February 28, 2002).

5.) Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1981.

6.) Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species, Bantam Books, New York, 1999.

7.) Paul Davies, “Taking Science on Faith,” The New York Times, November 24, 2007.

8.) Phillip E. Johnson, Darwin on Trial, 2nd ed., InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, Illinois, 1993.

9.) Randal Keynes, Darwin, His Daughter, and Human Evolution, Riverhead Books, New York, 2002.

10.) C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1952.

11.) Richard Milner, “What’s It All About Alfred?,” Natural History, February 2002.

12.) John Myers, Voices from the Edge of Eternity, Spire Books, Old Tappan, New Jersey: 1968.

13.) Peter Quinn, “The Gentle Darwinians,” Commonweal, March 9, 2007.

14.) The NIV/KJV Parallel Bible, Zondervan Bible Publishers, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1983.

15.) Judith Ann Schiff, “Learning by Doing,” Yale Alumni Magazine, November 2000.

16.) Dr. William W. Wassynger “Letters” section of The New York Times, December 15, 1989.

17.) Webster’s New World Dictionary, College ed., World Publishing Co., New York, 1964.

18.) World Magazine, February 26, 2000.